House Bill 589, “Competitive Energy Solutions for NC,” would be a major restructuring of energy policy in North Carolina. Here is a brief look into select aspects of the bill (third edition, as of this writing).

Part I. PURPA contracts

This portion of the bill addresses a serious issue for consumers. North Carolina’s unique implementation of the federal Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 (PURPA) is widely acknowledged to be the main reason this state, despite no particular geographic distinction from all other states, is “No. 2 in solar.” For background, see my report on “Reforming PURPA Energy Contracts.”

PURPA requires that electric utilities must buy any power generated from qualifying renewable facilities in their territory, regardless of need, as long as the qualifying facility can deliver its power to the utility. North Carolina has 60 percent of all PURPA qualifying facilities in the nation from which utilities have no choice but to buy from, regardless of need. Its contract terms are a major reason why.

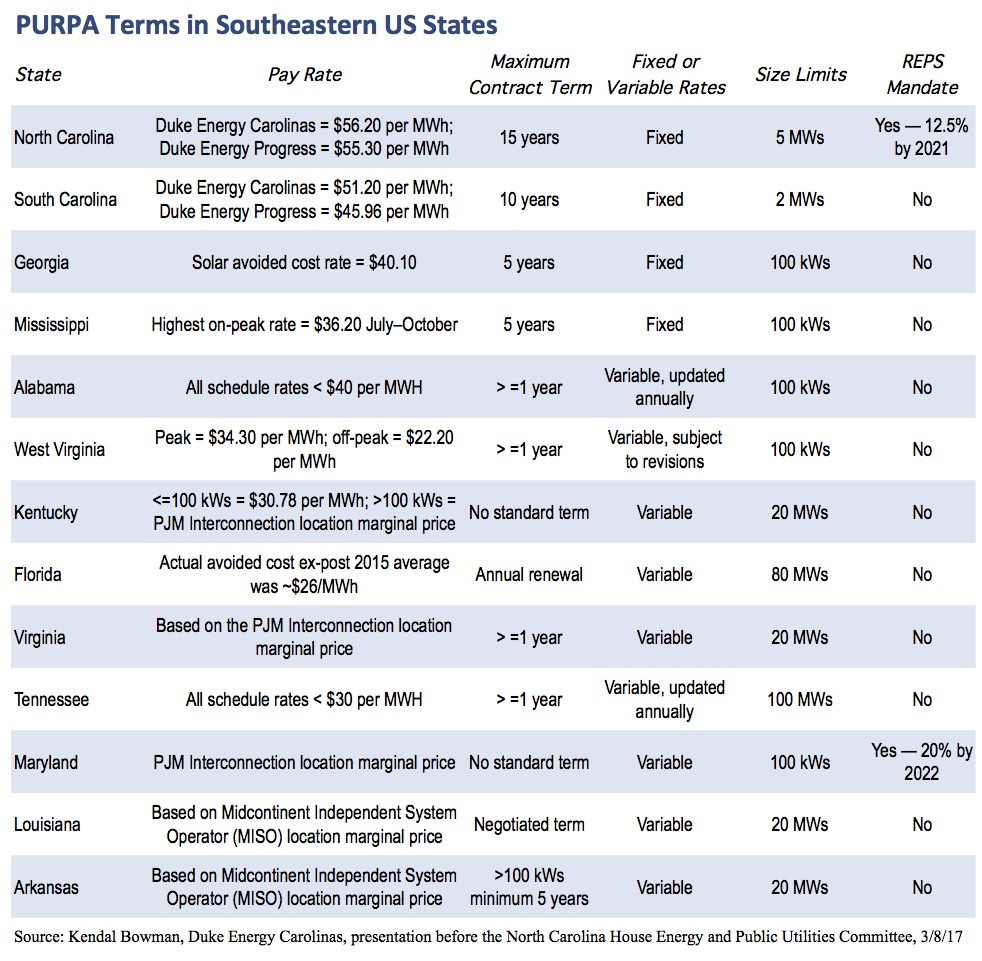

North Carolina has the highest avoided-cost rates of any state in the Southeast United States.

Avoided-cost rates are the contract price utilities pay for the renewable energy they must buy regardless of need because of PURPA. They are set at essentially the utility’s marginal cost, which is to say, the highest cost.

Furthermore, at 15-year terms, North Carolina has the longest contract terms of any state in the Southeast U.S., and at fixed rates no less. North Carolina also allows qualifying renewable power facilities to be up to 5,000 kilowatts (kWs; i.e., 5 megawatts or MWs) in size even as many other states are at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission minimum of 100 kWs.

The NC Utilities Commission (NCUC) has repeatedly resisted changing how avoided-cost rates are set, reducing contract terms, and lowering the size limits on qualifying renewable energy facilities. These decisions are regarded as victories, not for consumers, but for the solar energy industry.

HB 589 would reduce the PURPA contract lengths to a maximum of 10 years and the qualifying facility size to 1,000 kWs (1 MW) at first. Then, after reaching a threshold of 100 MWs of qualifying renewable energy under contract per public utility, the terms would be reduced to fixed five-year terms for qualifying facilities of 100 kWs.

These would be very important reforms. If the bill did nothing else, these are things consumers very much need to avoid being stuck with up to $1 billion in unnecessary electricity cost increases.

In terms of the bill title, making energy prices more competitive for consumers would make such reforms.

Unfortunately, consumers would still have to pay part of those unnecessary cost increases. Why? Because the bill includes a grandfather clause and deadline extension, which would let solar facilities in the works remain eligible for 15-year fixed rate contracts beginning as late as September 10, 2018. That unnecessary combination would lock in exorbitant prices well into 2033. That would detract from otherwise strong reforms for consumers and competition.

Furthermore, this reform does not revisit avoided-cost rates. NC would continue to have the region’s highest avoided-cost rates by far. That reality features prominently in the competitive procurement process in Part II.

Part II. Have renewable energy resources bid for contracts with utilities

This section would require Duke Energy and Duke Energy Progress to take bids for an aggregate 2,660 MWs of specifically new renewable energy over a 45-month period, plus an additional 3,500 MWs of renewable energy and any remnant not under contract under Part III below. At the end of that 45-month period, Duke would be required to open a second round of bidding for any part of that amount they don’t have under contract. This “competitive procurement” process would be administered by an independent third party.

Bids from renewable energy resources could not exceed utilities’ avoided-cost rate (i.e., their highest cost). Without the PURPA contracts reform in Part I, utilities would have to purchase all PURPA qualifying renewable energy resources coming online whenever they do, and all at the avoided-cost rate.

The contracts would be for 20 years, at fixed rates. These contracts would leave the utilities the ability to dispatch and control the renewable energy resources as they do their other generation sources in terms of dispatchability, siting, reliability, efficiency, system congestion, etc.

Giving the utilities ability to dispatch and control the renewable energy capacity they take on under these contracts would be an important change from the large must-take obligation under North Carolina’s implementation of PURPA. Barring any change, by 2020 the amount of intermittent renewable capacity Duke would have to take under PURPA would sometimes displace base load units at minimum capacity, an expensive outcome to Duke and by extension, their customers.

The amount of the capacity that this part requires utilities to seek from renewable energy facilities is extremely large. It creates an enormous set-aside for renewable energy.

Also, the capacity numbers in the bill are not random, either. The figure of 3,500 MWs, for example, is the amount of renewable energy considered to be either already on line or currently in the works.

Also, the total of all renewable energy capacity in this bill is about 6,800 MWs, which is the maximum level of solar capacity Duke believes its operations in North and South Carolina could take on and still maintain reliable operations. It derives from a 2014 study prepared for Duke by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

This bill would have that extreme case scenario built in, which means the upper bound price of the avoided-cost rate becomes extremely important for consumers worried about price impacts on their electricity bills. As mentioned above, North Carolina has the highest avoided-cost rates in the Southeastern U.S. by far. They are 10–20 percent higher than the next nearest state’s (South Carolina).

Bringing North Carolina’s avoided-cost rates more in line with surrounding states’ would prevent consumers from being harmed by utilities taking on such an enormous capacity of renewable energy at prices that could drift up into the region’s highest avoided-cost rates.

The move toward competitive procurement and away from uniquely generous PURPA terms would significantly reorganize the relationship in NC between solar energy facilities and utilities (and by extension, their customers):

NOW: Utilities must buy any renewable energy from a qualifying PURPA facility in their area, whenever the energy comes available and without respect for system needs at the moment, at 15-year, fixed avoided-cost rates (highest) contracts. Over time, this must-buy obligation will grow worse, crowding out even minimum base load units, indefinitely, as solar facilities continue to increase while PURPA enforcement in NC and other public policies extending favoritism to solar facilities remain unchanged.

UNDER THIS BILL: Utilities must offer to contract with any renewable energy facility in NC and SC that can sell energy below and up to avoided cost (highest), at the utilities’ dispatch and control discretion as with other generation sources, under 20-year, fixed-rate terms. The contracted capacity would be set at the maximum amount of renewable energy capacity that a Duke Energy Carolinas study estimated Duke can bring on while still maintaining reliable operation in the Carolinas.

The effect of this section on consumer energy prices depends on how it works in concert with Part I reforming PURPA contracts.

Its effect for renewable energy facilities is obvious. Basically, it presumes all expected renewable energy capacity in the near future should be in the generation mix. Will such presumption affect bid prices? Would renewable energy resources realize they are an oligopoly and therefore all bid at avoided-cost?

From this vantage point, the extent to which this part could be a net help to consumers would depend on how far below current avoided-cost rates renewable energy facilities are able to bid. Two ways that can happen:

- The capacity amount under competitive procurement for which renewable energy facilities would be bidding should be set below, not at, the total amount of renewable energy capacity expected in the coming years. Unless facilities bid against each other, it is not a competitive process, in which case there would be no reason to expect bids below the highest allowed.

- North Carolina’s avoided-cost rates should be lowered to bring them more in line with avoided-cost rates across the region.

Part III. Renewable energy programs on military bases, UNC campuses, and others

This portion of the bill would allow military bases, campuses in the University of North Carolina system, and other large-scale consumers of electricity contract with a renewable energy facility of terms from two to 20 years for energy. They would pay their normal retail bill plus the cost of the renewable energy purchased, then they would receive bill credits, not above avoided-cost rates for the energy used.

This five-year program would include 600 MWs of total capacity, setting aside 100 MWs for military bases and 250 MWs for UNC. Any that isn’t under contract by program’s end would be added to the 3,500 MWs renewable energy Duke would have to bid and rebid for in Part II.

The bill stipulates that nonparticipating consumers would be held neutral in rate costs regarding this part.

Federal (especially Obama era) mandates and national security concerns are involved with military bases’ energy needs. UNC schools’ energy policies are, however, matters of state taxpayer and UNC community members’ concern. Furthermore, programs such as these tend to expand utilities’ costs in ways that bleed past statutory promises to hold other consumers harmless.

At the very least, this section needs to be tightened up to include oversight over UNC purchases and to eliminate the rollover portion of any uncontracted renewable energy from the 600 MW set-aside.

Where it errs, it errs on the side of promoting the interests of a specific industry, not the side of making energy prices more competitive for consumers.

Part IV. Increase the fuel rider to pay for the renewable energy procurement

This part would allow the fuel cost rider to grow up to 25 percent faster per year (from 2 percent of the utility’s revenues to 2.5 percent) to recover the cost of PURPA-required renewable energy purchases and the nonadministrative costs of the program in Part III (i.e., nonparticipating consumers aren’t held “neutral”).

In all likelihood, this would not make energy prices more competitive for consumers.

Part V. Lower residential consumers’ REPS rider cap by $7/year

This part would, of course, go a small way in limiting residential consumers’ bills. It would lower their REPS cap from $34/year to $27/year but leave in place commercial customers’ REPS cap ($150/year) and industrial customers’ REPS cap ($1,000/year).

It’s a pro-consumer gesture, welcome as far as it goes. To be sure, however, the costs of compliance with the REPS mandate far exceeds the rider. This section is a symptom of the need to cap and sunset the REPS mandate.

Part VI. Third-Party Sales and Net Metering

This section of the bill would open electricity sales to consumers from something other than the designated utility monopoly in an area. That something would be limited only to solar energy facilities, however.

This section would be opening some choice and competition in the electricity market, however. Broadening consumer choice is important not only for allowing consumers to choose lower-cost options, but also to let consumers choose according to their particular values.

Think of how people make other purchases. Some, if not most people, prioritize saving money for their families over everything else. Others, however, choose to support causes they believe in or “buy local” from friends and neighbors. Choice in energy provision opens ways for people who would rather pay more to support solar energy or to support the local energy producer.

This part of the bill would allow consumers to contract with solar developers (or the utility, with certain limitations) for leasing eligible solar facilities to offset no more than 100 percent of their own electricity consumption.

It would also require revised net metering rates that would have participating customers pay fixed costs of energy and demand. That stipulation avoids the inequity problem in some states’ programs whereby participating customers are credited with retail rates on their bills for excess generation that doesn’t take into account grid maintenance and other fixed costs, which get shouldered by nonparticipating customers (who are often poorer).

This part of the bill also has a good section on consumer protection, which addresses another problem with some states’ programs whereby disreputable companies take advantage of unsuspecting, well-intentioned consumers with incomplete or misleading information or poor workmanship or both.

It also sets processes for community solar programs and solar leasing programs for municipalities. Both those sections would hold nonparticipating consumers harmless for program costs, as far as those guarantees go.

Overall this section would expand choice in energy for consumers.

Part VII. Speed up contracts for utilities buying energy derived from pork and poultry waste

Part of coalition-building to pass the REPS mandate in 2007 involved getting agricultural interests on board, so North Carolina included an unprecedented hog and chicken waste energy requirement that has proven nigh on impossible to implement practically. No other state does that. Its costs have so far proven exorbitant.

This section would make the NCUC expedite the process of reviewing these projects for mandated interconnection with utilities for providing their portion of the REPS mandate, regardless of the price feasibility of those projects.

This part furthers an obviously unworkable special-interest mandate that demonstrably wouldn’t make energy prices more competitive for consumers.

This section is a symptom of the need to cap and sunset the REPS mandate.

Part VIII. Pay consumers to participate in net metering

This part would require the utilities to offer rebates to induce consumers to install or lease solar facilities and participate in net metering. The bill would let the utilities recover those costs through the REPS rider. So, consumers who don’t participate — or can’t — are the ones who would fund it.

This part basically subsidizes a specific consumer choice for a specific product by consumers who wouldn’t make that choice for themselves.

It has nothing to do with making energy prices more competitive for consumers.

General Recommendation: Cap and sunset of the Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard mandate (REPS)

Forcing consumers to purchase, via their only electric utility (whether it is a large public utility or an electric membership corporation or municipal utility), more expensive energy from a favored industry is the antithesis of competition. Furthermore, the continued existence of the REPS mandate means its more unworkable provisions — especially those concerning pork and poultry waste energy facilities — still apply, in sore need of a legislative workaround.

It’s a key oversight that should be addressed in the debate over the bill.

General Recommendation: Study how to set avoided-cost rates more in line with surrounding states’

Reforming PURPA terms (Part I) and transitioning to a competitive procurement process (Part II) is a significant reorganization of relationships between renewable energy facilities, utilities, and their customers. How much of it would help consumers? A lot would depend on how far below current avoided-cost rates renewable energy facilities are able to bid.

Why are North Carolina’s avoided-cost rates set so high? How much would it benefit consumers through lower energy prices and lesser rate increases by transitioning to avoided-cost rates more in line with other states’?

Especially if the set-aside under the competitive procurement process of Part II is so broad that it basically makes renewable energy facilities into an oligopoly, revisiting avoided-cost rates would be very important.

Summary

For consumers, the most important piece of this bill is Part I, which addresses North Carolina’s significant problem with PURPA contract lengths and qualifying facility sizes. It does not address North Carolina’s high avoided-cost rates, however.

Part II, which sets up a competitive bidding process for basically all expected renewable energy capacity in the near future, would offer renewable energy facilities a very cushioned landing from the PURPA reform. Its ultimate effect on consumers would depend on how far below current avoided-cost rates renewable energy facilities bid. Right now, those rates are the highest in the region.

Part VI regarding third party sales and net metering also expands choice and competition for consumers in ways that avoid problems many other states’ programs have suffered from.

The lack of a cap and sunset of the Renewable Energy Portfolio Standards mandate is a key oversight. Its absence factors in some of the bill’s sections.

Most of the other policies in this bill are geared toward helping solar energy facilities with a little boost for unworkable hog and poultry waste energy facilities.