North Carolina doesn’t have a doctor shortage. Doctors just aren’t choosing to practice medicine in sparsely populated towns.

“The real problem is maldistribution,” says Dr. Erin Fraher, Director of the Program on Health Workforce Research and Policy at the University of North Carolina. Fraher presented before lawmakers this week at a subcommittee meeting on graduate medical education (GME) and residency. “I do not believe that this state faces an overall physician shortage,” she adds. “It faces a shortage of physicians in the right communities and the right specialties.”

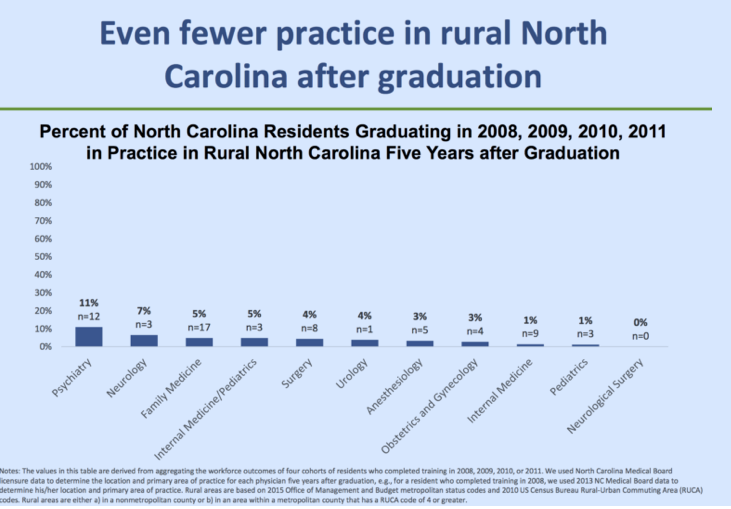

While the supply of physicians is indeed increasing across North Carolina relative to population growth, Frahrer further points out that only five percent of family doctors who graduated from residency programs between 2008 and 2011 are practicing in rural areas.

Scoping Out Health Policy Reform

As legislators are considering policies that aim to bring better health care access to North Carolinians, one of Fraher’s recommendations was for the state to hold accountable academic medical institutions in how they spend taxpayer-funded GME money. More transparency will also uncover how effective residency programs are at retaining physicians to practice rural medicine.

Keep in mind that GME reform is just one of many regulatory changes that can alleviate the widening urban-rural health disparity. Others that were briefly mentioned during the meeting included telemedicine and scope of practice reform, in which nurse practitioners (NPs) would be able to practice to the full extent of their training without physician oversight. This week’s rural health committee meeting will be hearing from a panel of speakers on this very issue. Scope of practice reform never fails to make for a lively debate.

Scope of Practice

If an NP wants to practice in North Carolina, he/she must establish a collaborative practice agreement with a physician that outlines practice parameters for patient management and prescribing authorities, as well as describing how the providers will interact. Interestingly enough, NPs don’t have to be in the same geographic location as the overseeing physician, and they are only required to meet twice a year.

The lack of oversight, then, begs the question of why these contracts are even necessary.

Decoupling the collaborative agreement would open opportunities for NPs to deliver patient care in more rural and underserved areas. Other states that have enacted such reforms are already seeing this trend play out. Arizona, for example, granted NPs full practice authority in 2002. Five years later, the state reported a 73 percent increase in the number of NPs practicing in rural counties. Moreover, studies show that advanced practitioner training enrollment is 30 percent higher in states that grant full practice authority.

Since NPs in North Carolina aren’t geographically tied to the collaborating physician’s practice location, you might think that the state’s existing practice arrangements wouldn’t necessarily hold NPs back from extending their reach into underserved areas. For some, it’s a non-issue. For others, these contracts add risk to their preferred practice style. Let’s look at a few scenarios:

- Scenario 1: An NP wants to open her own practice, but her collaborating physician moves to another state. The NP must now find another physician who is willing to sign onto a new collaborative practice agreement.

- Scenario 2: A hospital’s policy may prevent employed physicians from signing or renewing a collaborative agreement with an NP who is not affiliated with that hospital.

- Scenario 3: These contracts can be pricey, making it difficult for some nurse practitioners to grow their own clinics. A source relayed to me that one NP in the state would like to bring on another NP to work at her clinic, but can’t afford to do so because her collaborating provider asks for a specific percentage of her clinic’s revenue.

NPs are valuable assets to the health care workforce. Of the 6,152 who are licensed in North Carolina, most practice in a primary care setting and focus on managing chronic disease. So, why continue to tether NPs to the physician maldistribution North Carolina faces? If NPs were liberated from collaborative agreements, they would then have the option to fill in some of the access gaps at a faster pace compared to physicians because it takes a lot less time and money for them to complete their educational and clinical training. Based on health care workforce projections between 2010-20, the number of fully trained NPs is expected to increase by 30 percent compared to an 8 percent rise in the number of physicians.

At a time where supply-side reforms are most necessary in health care, it would be a good idea for lawmakers to revisit House Bill 88, the Modernize Nursing Practice Act, once the legislative short session begins in May.