Abstract

Abstract

North Carolina is one of 18 states that do not have a telemedicine parity law, which forces insurance companies to pay health care providers for services treated via telemedicine that are otherwise covered during an in-office visit. While most states have such laws, their unintended consequences perpetuate the worst features of our nation’s health care system. Parity laws may impede the creation of a treatment plan that meets the needs of individual patients, raise costs, and conceal the cost of care from the consumer. Telemedicine is thriving in nonparity states like North Carolina, suggesting that the cost and burdens imposed by telemedicine parity laws would likely exceed any benefit.

Introduction

Despite Congress’ inability to pass meaningful health reform, an ongoing dialogue focuses on how patient access to health care can be improved. Patients not only wait an average 19 days to be seen by a family physician, but they also experience less time with their provider during an in-office visit.1 This is, in large part, due to the growing demands of older patients, an influx of newly insured patients, and the national primary care work force shortage.2 3

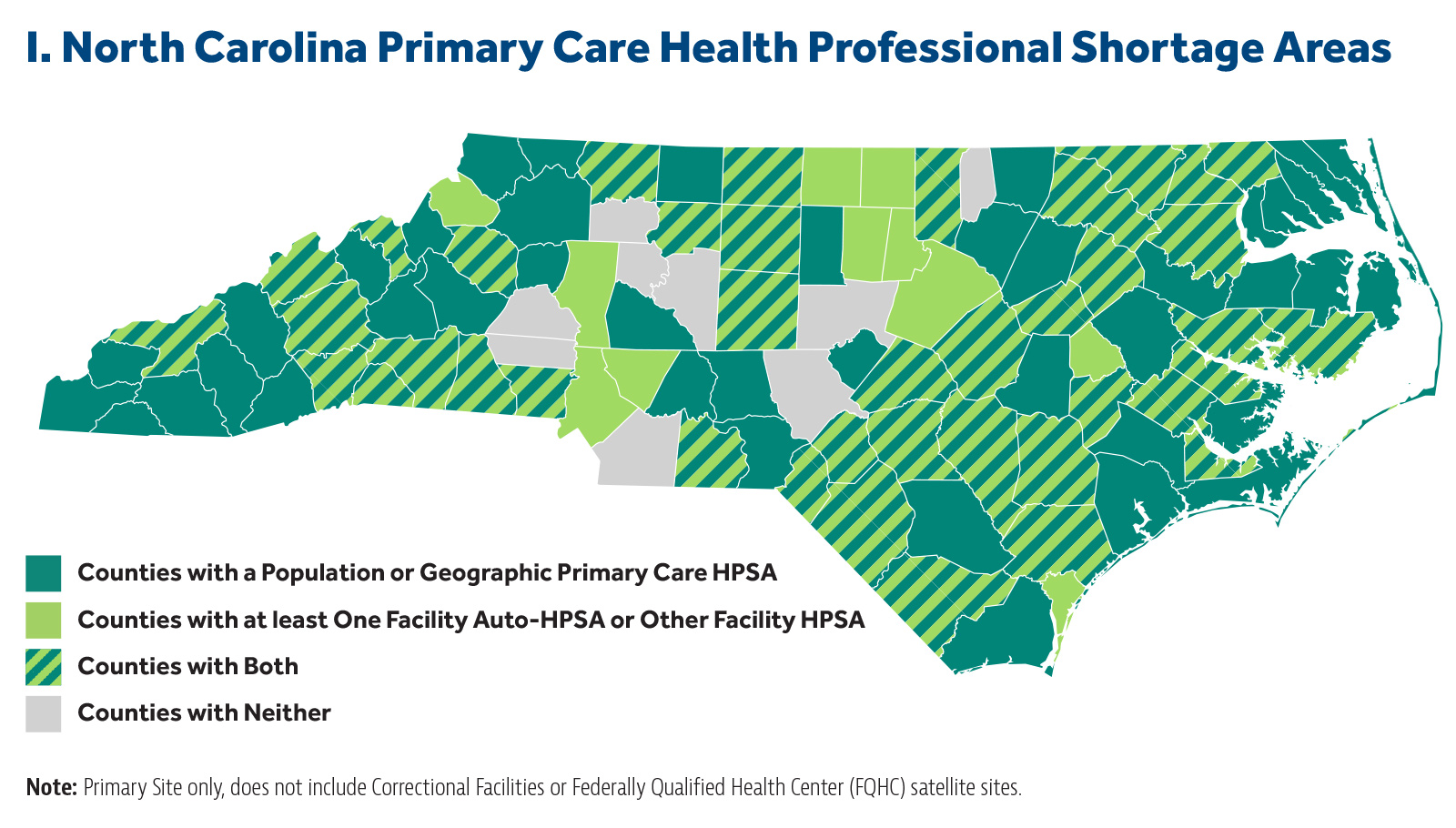

Accessing a health care provider is even more difficult for patients living in rural areas. According to the Health Resources and Services Association, 20 percent of Americans reside in rural areas, and just 11 percent of the nation’s physicians practice rural medicine.4 North Carolina alone has documented 145 primary care shortage areas 5 across the state.

Whether or not Congress reaches a consensus on policies that address gaps in health care access, it’s important to emphasize how the market is responding efficiently to this critical issue. Telemedicine, a multibillion-dollar industry, is a leading innovation that has proven to expedite the delivery of health care.

Overview of research on telemedicine

Defined as “the use of technology to deliver health care, health information, or health education at a distance,” telemedicine helps people connect more quickly to their primary, specialty, and tertiary medical needs.6 Its early beginnings trace back to the late 1800s, when providers began using the telephone to resolve patient consults at a distance, saving them from making time-consuming house visits.7 8

Telemedicine is versatile in that it delivers health care through various methods or modalities. For example, virtual telemedicine allows patients to interact in “real time” with their medical provider through secure video apps or telephone. Communication occurring in real time between a patient and a provider is called synchronous telemedicine. Asynchronous, or “store and forward” telemedicine, lets patients send information about nonurgent health issues for providers to evaluate later. It is “asynchronous” because the parties are communicating with one another at different times. Online vision tests and messaging platforms that permit secure correspondence between patients and their physicians are just a few examples of asynchronous telemedicine.9 10

Lastly, many hospitals are investing in remote patient monitoring (RPM) projects to cut down on readmissions penalties, length of stay, and patient mortality, all of which affect overall hospital costs. With RPM, flagship hospitals are partnering with rural intensive care units (ICUs) and emergency departments to assist in monitoring some of the most vulnerable patients.11

As case studies and statistical analyses illustrate the benefits of telemedicine, more rigorous evaluation and data are needed to determine its overall impact on health care cost, quality, and access.12 That said, disciplines that assess the impact of technology on institutions and enterprises encounter the same problem: Advancements in technology often outpace the production of peer-reviewed research. By the time such research is published, the technological landscape has likely changed in a way that limits practitioners’ and policymakers’ ability to employ its findings. That is why policy studies and industry reports are critical to the study of activities that employ advanced technologies.

The amount of academic literature on telemedicine is growing, however. A Cochrane review of 93 randomized control trials concludes that the intervention of different telemedicine functions is particularly effective for patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease. With telemedicine treatment, patients suffering from congestive heart failure experienced better quality of life compared to patients without telemedicine treatment. Meanwhile, blood sugar, blood pressure, and bad cholesterol levels declined among diabetic patients who engaged in telemedicine compared to those who received traditional care.13

Research also shows that telemedicine helps reduce depression levels for patients who access psychiatrists and psychologists at a distance compared to patients who receive mental health treatment from on-site primary care providers and nurse managers.14 Patients diagnosed with depression are also engaged in more self-management activities as encouraged by telehealth providers.

Telemedicine parity laws: Research and trends

To date, 32 states have enacted telemedicine parity laws, all of which were created to meet the unique needs of their states’ insurance and health care systems. 15 16 In some states, reimbursement is restricted to certain types of providers and site locations. This is because health plan designs must be consistent with the state’s definition of telehealth and how the practice of telemedicine is regulated under state medical licensing boards. Georgia, for example, defines physicians, advanced nurse practitioners, and physician assistants as eligible telemedicine providers.17 Tennessee’s telehealth definition permits private insurers to pay for telemedicine if it’s delivered in “qualified sites,” such as hospitals, federally qualified health centers, rural health clinics, medical offices, or any other location deemed acceptable by the insurer.18

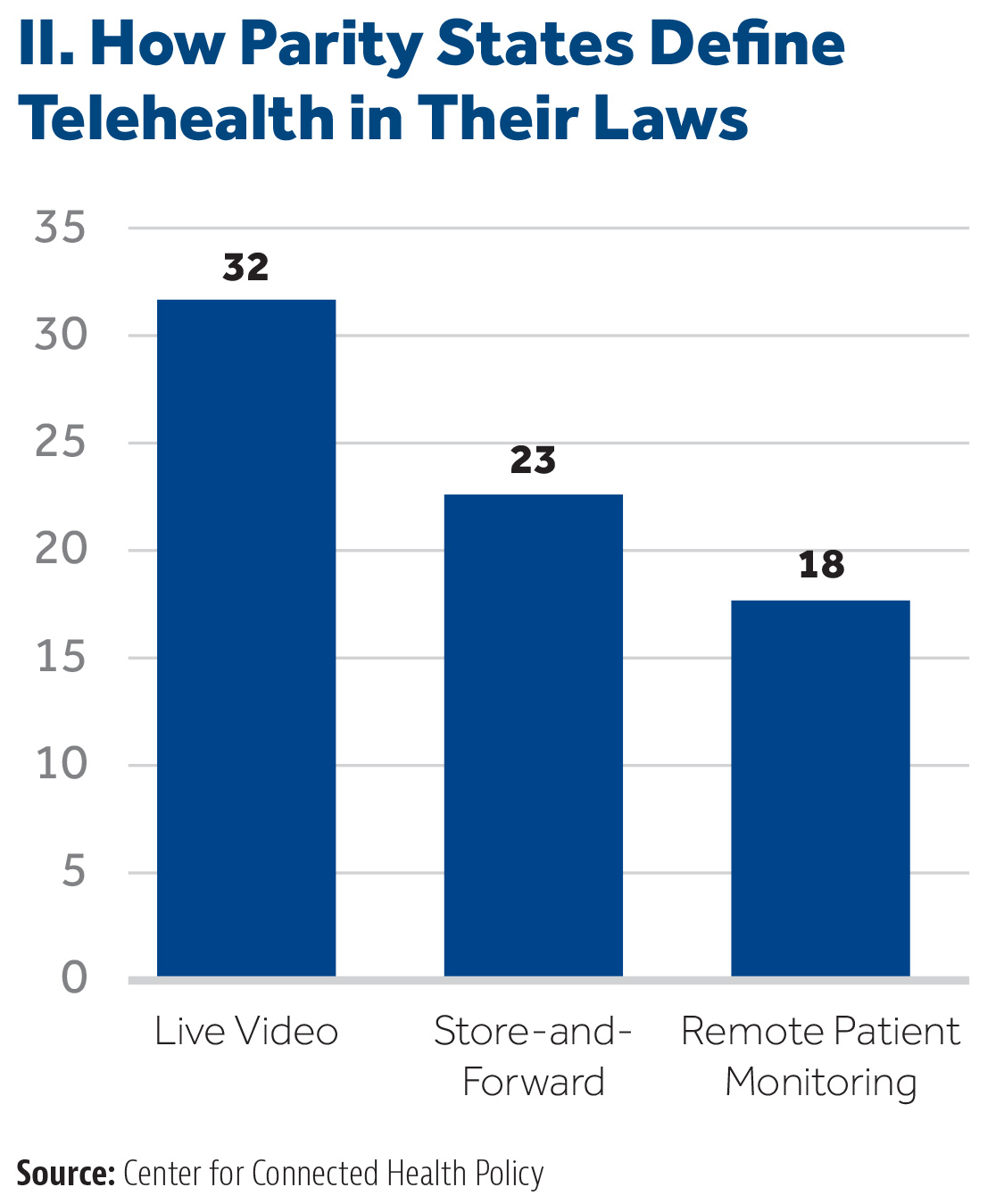

The lack of uniformity across states’ rules on telemedicine also impacts the types of telemedicine that providers can use for patient care. According to the Milbank Foundation’s assessment of state telemedicine parity laws, all require virtual visits to be covered. Seventy-two percent also recognize services delivered through asynchronous or store-and-forward platforms, while just over half mandate remote patient monitoring.19 See Chart II.

For example, Tennessee’s description of telemedicine specifically references technologies that facilitate both virtual/synchronous and asynchronous telemedicine between patients and licensed medical providers.20 Some states have sought to expand the delivery of telehealth by not changing their definitions of telehealth, but instead amending their existing parity law language. In 2014, Mississippi’s telemedicine law was reinforced so providers can now bill for remote patient monitoring.21

For example, Tennessee’s description of telemedicine specifically references technologies that facilitate both virtual/synchronous and asynchronous telemedicine between patients and licensed medical providers.20 Some states have sought to expand the delivery of telehealth by not changing their definitions of telehealth, but instead amending their existing parity law language. In 2014, Mississippi’s telemedicine law was reinforced so providers can now bill for remote patient monitoring.21

Variations across state parity laws also make it possible for private health insurers to have flexibility in determining which telemedicine services they choose to cover. If statutory language states that an insurer shall pay for telemedicine benefits based on its “terms and conditions,” then the insurer arguably has more discretion over what telemedicine services are deemed appropriate for reimbursement.22 Parity law language in states such as Kentucky and Georgia share similar “terms and conditions” clauses.23 24 Others are not as fortunate, meaning that state governments may have more leverage in dictating what types of telemedicine is to be paid for.

Telemedicine parity and unintended consequences: Compulsory adoption of delivery systems, higher costs, and overconsumption

Overall, parity laws can be classified as either “partial” or “full.” Partial parity is defined as when a private insurer must cover a treatment delivered via telemedicine “on the same basis” as when provided in person. In other words, partial parity laws don’t require insurers to incorporate more health services. They only request that insurers reimburse providers when using telemedicine to treat patients for services that are otherwise covered during an in-office visit.25 Both Virginia and Georgia are examples of states with partial parity laws that share “on the same basis”26 coverage language.27

Nathaniel Lacktman, health care lawyer and telemedicine parity law expert, provides further context:28

The laws do not mandate the health plan provide entirely new service lines or specialties. The scope of services in the plan’s member benefits package remains unchanged. The only difference is that the patient can elect to see his or her doctor via telehealth rather than driving to the doctor’s waiting room.

On the other hand, “full parity” forces insurers to pay providers for services treated via telemedicine at the same rate those services are billed for in an office setting.

The concept of partial parity seems to contradict private insurers’ concern that these laws resemble another health benefit mandate. However, further examination on the evolution of parity laws does indeed add credibility to private insurers’ opposition. Parity laws set a precedent for state governments to further meddle in private enterprise by forcing insurers to pay for other telemedicine services that are beyond the scope of their original plan design.

As previously mentioned, in 2014, Mississippi made its parity law more comprehensive by mandating that private insurers pay for remote patient monitoring (RPM), a form of telemedicine that allows health care providers to monitor chronically ill patients who are homebound.29 30

Insurers typically do not reimburse for RPM. Since its passage, health systems like the Mississippi Medical Center extended its telehealth program to establish an RPM network for diabetes patients. Early reporting on health outcomes among 100 patients found a 96 percent medication adherence rate and fewer hospitalizations. Program advocates claim that, because of RPM services such as health coaching and continuous wireless glucose monitoring, insurance carriers saved over $300,000.31

While the program produces positive results, it’s important to emphasize that payers, not the government, should have the freedom to choose which telemedicine services to invest in.

Interviews conducted between the Center for Connected Health Policy and insurance representatives who are subject to parity laws affirm this concern: 32

When asked if they considered expanding their current telehealth policies, several interviewees voiced caution. They noted concerns about efficacy in certain interactions. Most preferred a slower, more thorough approach to expansion that could include their own pilot projects before considering larger changes. While we did not sense any reluctance on the part of interviewees to move forward with telehealth, it was evident that the interviewees only wanted to reimburse for services for which they felt telehealth could appropriately be used, such as routine office visits.

Kentucky, the first state in the nation to pass a telemedicine parity law, is also subject to stringent coverage rules. Payers are required to cover services performed by in-network health care providers who are affiliated with the state’s Telehealth Network. Established in 2005, the Kentucky Telehealth Network has expanded statewide to offer patients health care services at 200 facilities. Payers only have discretion over telemedicine when services are rendered outside the telehealth network.33 34 35

In addition, equal payment certainly acts as a strong incentive for more physicians to adopt telemedicine platforms. However, enforcing such a rule undermines telemedicine’s cost-effective capabilities.36 Compared to an average $146 office visit, a patient can connect with a physician virtually for $79.37

Full parity not only prevents telemedicine from being cost-effective, it also shields patients from the actual cost of care. A lack of price transparency across the nation’s health care system is what keeps health care costs high. Where price transparency does exist in the health care space, the telemedicine market has proven that most primary care needs can be affordable when paid for out of pocket.

Lastly, telemedicine parity laws diverge from the trend in which third-party payers are increasingly paying providers based on health outcomes rather than the volume of services rendered. Providers who are paid capitated rates, or a defined amount per month, are more likely to adopt telemedicine as an additional tool for patient care38 because they don’t need to concern themselves with getting paid separately for these services. Under a payment model that rewards value over volume, providers have more of an incentive to be creative in how they care for their patients. Telemedicine is one benefit that fits in nicely within this payment arrangement.39

In the end, telemedicine parity laws perpetuate the shortcomings of our current health care system. They may disincentivize the creation of a treatment plan that meets the needs of individual patients. They may raise costs and conceal the cost of care from the consumer. And they may encourage the overconsumption of health care by paying providers based on the volume of services and not outcomes.

Telemedicine is Thriving in North Carolina and Nonparity States

For the convenience that telemedicine offers without compromising the quality of care, some medical providers are still resistant to adopting the practice because certain services don’t always come with insurance reimbursement. Such pushback is one of the reasons why 32 state legislatures have passed telemedicine parity laws. 40 41 Telemedicine parity laws force private insurance carriers to cover treatment via telemedicine that is otherwise covered during an in-office visit.

Yet, it’s a false notion to think that a state is lagging in health care innovation if it has not enforced a parity law. North Carolina and surrounding nonparity states in the Southeast are in fact engaged in many telemedicine initiatives that span multiple levels of care.

Innovation in North Carolina

North Carolina’s legislature has not enacted a telemedicine parity law, but in 2017 it passed legislation that directed the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to produce a report42 assessing the telemedicine landscape in North Carolina and offer policy recommendations on how to expand telemedicine’s reach to more patients.43 One of those policies listed is “private-payer telemedicine reimbursement standards.”

The DHHS report that was submitted in October 2017 does not provide definitive suggestions regarding private-payer telemedicine laws. In fact, the report specifically asks for the N.C. Department of Insurance to weigh in with its own comments.

It is admirable the General Assembly wants to advance legislation that encourages more medical professionals to adopt telemedicine so patients can access care without having to travel long distances. Telemedicine private-payer laws are well-intentioned and generally receive overwhelming bipartisan support. However, private insurers are likely not to endorse yet another law that further erases their authority in designing health plans. Enacting telemedicine parity only adds to the growing list of health benefit mandates44 insurers must include in their small-group and individual consumer policies.

To that end, it’s important for state policymakers to be fully informed about these laws and be mindful of how they conflict with market-oriented health policy principles.

Private Insurance Companies

Most of the state’s major private insurance carriers are offering virtual telemedicine services through either an in-house platform or other vendors. As early as the mid-1990s, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina (BCBS NC) provided telemedicine benefits for psychiatric care, psychotherapy, health behavior assessments, and diabetic counseling.45 Meanwhile, UnitedHealth Group began covering virtual visits for their policyholders in 2015.46

BCBS NC has also partnered with telemedicine startups that aim to prevent unnecessary visits to the emergency room and other costly health care settings. Mosaic Health, a subsidiary of BCBS NC, invested $4 million in TouchCare, a company based in Durham, N.C.47 48 Like many telemedicine apps, TouchCare connects patients to physicians through a secure virtual platform. Patients can download the app at no cost and gain access to providers at FastMed Urgent Care locations and mental health providers affiliated with Carolina Partners.

Compared to government payers, private insurers operating in North Carolina and other states grant providers and patients more flexibility in how virtual visits are conducted. Both UnitedHealth Group and Blue Cross, for example, allow patients to use telemedicine platforms to connect with an in-network physician from any location, including work or home.

North Carolina’s Medicaid program, meanwhile, reimburses providers for virtual patient encounters only if the patient is located at a “sufficient distance” from the provider. Medicaid also requires eligible telemedicine providers to seek prior approval before treating patients through an online platform.49

Medicare reimbursement limitations are even more stringent. Only beneficiaries who live in rural health professional shortage areas can access telemedicine services, and they must be present in a “qualified originating site,” such as hospitals, physician offices, rural health clinics, community mental health centers, and certain long-term care facilities.50

Price Transparent Physicians

Whether or not insurers reimburse for telemedicine services, some physicians are proving that health care needs provided through various forms of telemedicine are affordable when consumers pay for them out of pocket – again, eliminating the need for private-payer parity laws.

RelyMD

RelyMD is a telemedicine app founded in 2015 by an independent emergency physician group in North Carolina.51 52 The startup’s board-certified physicians offer 24/7 virtual doctor appointments to their users in exchange for a $50 per-visit fee. Patients can seek medical consultation or treatment in the comfort of their own homes via a computer, smartphone, or tablet in a matter of minutes. Not only is RelyMD convenient for a busy parent with a sick child who cannot wait an average 19 days to be seen in person by a family physician53, but the cost is also a significant discount compared to an urgent care visit or a minimum $1,000 trip to the emergency room.

RelyMD is now working with North Carolina’s community health centers to extend after-hours care when these facilities are closed. The partnership began in 2016 with Piedmont Health’s Scott Community Health Center in Burlington, N.C. One year later, RelyMD expanded its presence by contracting with 70 corporate clients and is currently available to patients who frequent all 10 of Piedmont’s locations spread across the central region of the state.54

Direct Primary Care

Health care providers who embrace the Direct Primary Care (DPC) model aren’t letting fee-for-service payment policies dictate how they practice medicine. They’ve opted out of insurance contracts altogether, freeing themselves from the rigid structure of billing codes, modifiers, and prior authorizations. Instead, they contract directly with their patients, providing all of their primary care medical needs in exchange for an average $75 monthly fee.55 Phone calls, texts, emails, FaceTime, secure messaging platforms, and specialty consults – the most common uses of telemedicine – are included in a patient’s membership package.

One of the defining characteristics of DPC is that these physicians keep their practices small so they can spend more time with their patients.56 Telemedicine further restores their physician-patient relationship by extending access to health care beyond the exam room.

Some DPC practices in North Carolina use Spruce Health, a secure messaging platform that lets these physicians have continuous conversations with their patients.57 They can respond to inquiries ranging from which vitamin D tablet to buy, to feedback on a diabetic patient’s reported blood sugars.

Platforms like Spruce include other features that improve physician workflow while keeping patients satisfied. For example, if a patient thinks he may have a sinus infection, he has the option to answer a pre-scripted questionnaire related to the diagnosis at his own convenience. Once completed, it is sent to be reviewed by the physician. This communication style not only caters to both the physician and the patient’s separate schedules, but it also provides for better documentation because the questionnaire and all physician notes are downloaded into the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR). Written documentation could lead to better patient adherence, given that patients tend to forget 80 percent of a physician’s verbal orders. Half of the patients that do remember end up interpreting them incorrectly.58

Another telemedicine benefit many DPC patients have access to at no additional cost to their membership are e-consults or online consultations for specialty care.59 When physicians question whether their patient’s condition is beyond the scope of their practice, e-consults give them guidance to determine if specialist referrals are necessary.

For $250 per month, physicians can seek medical advice on behalf of patients from more than 100 different specialties through RubiconMD. The company guarantees a response time of 12 hours or less.60

While various health care professionals use e-consults, this form of telemedicine pairs exceptionally well with DPC. E-consults assist DPC physicians in fulfilling their value proposition that most health care needs can be managed thoroughly in a primary care setting. And because they can spend more time with their patients, e-consults are a tool to help them reduce the 40 percent of specialist referrals that could, in fact, be managed by a primary care physician.61 The DPC model proves that practicing medicine is much more flexible when it bypasses the complexities associated with health insurance. They can be creative with designing primary care membership plans that feature built-in benefits that patients will value – like telemedicine.

Hospitals

As hospitals adjust to the shift from fee-for-service reimbursement to risk-based contracts, or when providers are rewarded or penalized based on cost savings and patient health outcomes, telemedicine is a powerful tool to help health systems achieve desirable results.

Carolinas HealthCare System Tele-ICU

The ongoing intensivist shortage62 combined with the difficulty of recruiting specialists to work in rural hospitals compelled Carolinas HealthCare System (CHS) to build a $12 million virtual care center in 2013. Located outside of Charlotte, the command center is staffed with intensivists and nurses who are responsible for remotely monitoring hundreds of patients’ vital signs and labs across 10 of the system’s intensive care units (ICUs).63 64

Given that ICUs now make up 30 percent of a hospital’s cost65, largely because these facilities care for the sickest patients, the command center’s additional layer of oversight has begun to pay dividends for CHS. The ability for remote providers to practice proactive medicine has helped lower the health system’s mortality rates by 5 percent and length of stay by 6 percent.66 Faster discharge rates also open beds within CHS’s rural hospitals to make room for higher volumes of patients. Perhaps what’s most important is that patients who are admitted to one of CHS’s rural ICUs can stay closer to home. In the absence of the command center’s extra sets of eyes and ears, they would otherwise be transported longer distances to CHS’s hub hospital to access a critical care specialist.67

UNC Health System ICU Partnership with Mercy Virtual

Another initiative established last year is the tele-ICU network between the University of North Carolina Health Care System (UNC) and Mercy Virtual, a $52 million “hospital without beds” located in Missouri.68 The hospital’s mission is to deliver health care remotely for patients in various settings. Within its multi-facility network, Mercy assists patients in the comfort of their own homes to avoid readmission penalties and unnecessary emergency room visits, to assess stroke victims at a distance, and to respond to provider teams at other ICUs.69 UNC’s partnership is significant in that it represents the first major hospital “spoke” outside of Mercy Virtual to connect to its “hub.” Mercy currently monitors 28 UNC Health Care ICU beds. Overall, Mercy’s program has already achieved significant declines in patient mortality and length of stay, generating savings upwards of $50 million.70

Telemedicine in Southeastern States Without Parity Laws

Alabama

The Alabama Stroke Care Network

Before Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama began covering tele-neurology services in 2015, Southeast Alabama Medical Center (SAMC) sought to improve the state’s ranking as having the worst stroke mortality in the nation. In 2011, SAMC began raising funds to develop the Alabama Stroke Care Network. The hospital’s foundation and philanthropic arm raised over $255,000 to pay for six telemedicine carts equipped with necessary resources to connect stroke victims in rural Alabama with neurologists working for SAMC and AcuteCare Telemedicine (ACT), a tele-stroke company headquartered in Atlanta.71 72 Within two years, the Stroke Care Network expanded to include five “spoke” hospitals across rural Alabama.73 Emergency room providers in these hospitals can now interact virtually with neurologists at SAMC and ACT to help assess stroke victims and administer clot-busting drugs. Hub hospitals can become recognized as certified Primary Stroke Centers.74 75

BCBS Alabama

To bring scarce resources to policyholders living in rural areas, BCBS Alabama now covers telemedicine for five types of specialty care: cardiology, dermatology, mental health, and infectious and neurological disease. The insurer began offering these benefits in 2015.76

Teladoc, one of the leading telemedicine companies in the U.S., has also contracted with BCBS Alabama to extend its urgent care consult services to group plan policyholders. For nonemergency medical visits, the company has been able to maintain a 95 percent patient satisfaction rate.77

Florida

MDLive

Florida is home to multiple telemedicine startups. MDLive, a national telemedicine leader, has secured $73 million in venture capital funding since its founding in 2009.78 One of its notable partnerships is with Cigna. Self-insured companies that contract with Cigna now offer MDLive’s 24/7 video consultations as a supplemental primary care benefit for employees.79 The company defines itself by providing expedited continuity of care, as each documented patient encounter is sent to an in-network primary care physician and uploaded into that patient’s electronic medical record (EMR). Depending on the total amount self-insured employers offset the costs for virtual visits, patients typically pay less than $60. Enterprises like MDLive can be valuable for employers’ workflow because research suggests that as much as 70 percent of patient consults can be handled outside of a physician’s office.80 81

MD Plus

Another direct-to-consumer telemedicine startup is MDPlus. Established in Clearwater, Florida, the company offers three different “around-the-clock” medical consultation plans for individuals and businesses. The basic plan, for example, costs $20 per month in addition to a $35 consultation fee when a customer connects with a health care provider for nonurgent medical needs.82 MDPlus also brings transparency to the health care market with its patient advocacy services. Representatives provide customers with price comparisons for medical procedures, equipment, and prescriptions.

South Carolina

A nationally recognized Center for Telehealth Excellence, the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) is known for its school-based telehealth program. Starting in 2013, a $12 million General Fund appropriation and a grant from the Duke Endowment has helped MUSC providers connect with students in more than 50 schools across the state.83 84 Schools are equipped with telehealth carts that come with computer monitors, digital stethoscopes, and otoscopes. With these tools, physicians can examine a student’s nose and ears and listen to his or her heart and lungs in real time from a distance.

Other hospitals in the state have launched school-based telehealth networks.85 Since 2015, one of Greenville Health System’s nurse practitioners makes on-site rotations at one of four elementary schools in Greenville. If a student needs a prescription and the nurse practitioner is not physically present, the school nurse can receive approval online by the nurse practitioner.

West Virginia

Anthem Blue Cross

Since 2016, Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield customers in West Virginia can engage in virtual visits with nurse practitioners affiliated with the Cleveland Clinic.86 Unlike other companies that offer virtual telemedicine services, Anthem’s policyholders can select their provider before their consultation.

iSelectMD

iSelectMD, another telemedicine consultation service, is now available to more than 180,000 members of West Virginia Public Employees Insurance Agency (PEIA). Members of PEIA include employees at school systems and universities, local governments, and other state agencies. iSelectMD’s licensed physicians aim to resolve patient consults within an average of 30 minutes.87

Telehealth Service’s SmarTigr Patient Engagement Program

With the help of Telehealth Service’s SmarTigr, a patient education program that is integrated into health systems’ smart TVs, Charleston Area Medical Center has been able to reduce hospital readmission rates for patients with heart and lung disease by 22 percent and 30 percent, respectively, in one year.88 This is a significant achievement, given that West Virginia leads the nation in prevalence rates for chronic illnesses. SmarTigr’s platform lets caregivers select educational videos for patients that pertain to their health issues, followed by comprehension “quizzes” on medication adherence and disease self-management. SmarTigr is a useful tool that not only enhances patient engagement but also improves health literacy.89

Policy recommendations

It is admirable that the General Assembly wants to advance legislation that encourages more medical professionals to adopt telemedicine so patients can access health care without having to travel long distances. However, the examples above illustrate that it’s a mistaken notion to view North Carolina and other nonparity-law states as lagging in telemedicine innovation. Lawmakers should also be fully aware of the unintended consequences that can result from parity laws.

While studies suggest that telemedicine delivers quicker, cost-effective health care without compromising quality, more research is needed to look at how private-payer laws impact the health insurance market. To that end, private insurers themselves should decide to invest in telemedicine services on behalf of their policyholders – not the government.

Instead of expanding telemedicine by imposing more regulations on insurance companies, North Carolina lawmakers should focus on the removal of licensure barriers that limit telemedicine’s growth. Lawmakers and regulatory boards should be commended for the progress that’s already been made in this regard.

Interstate Reforms

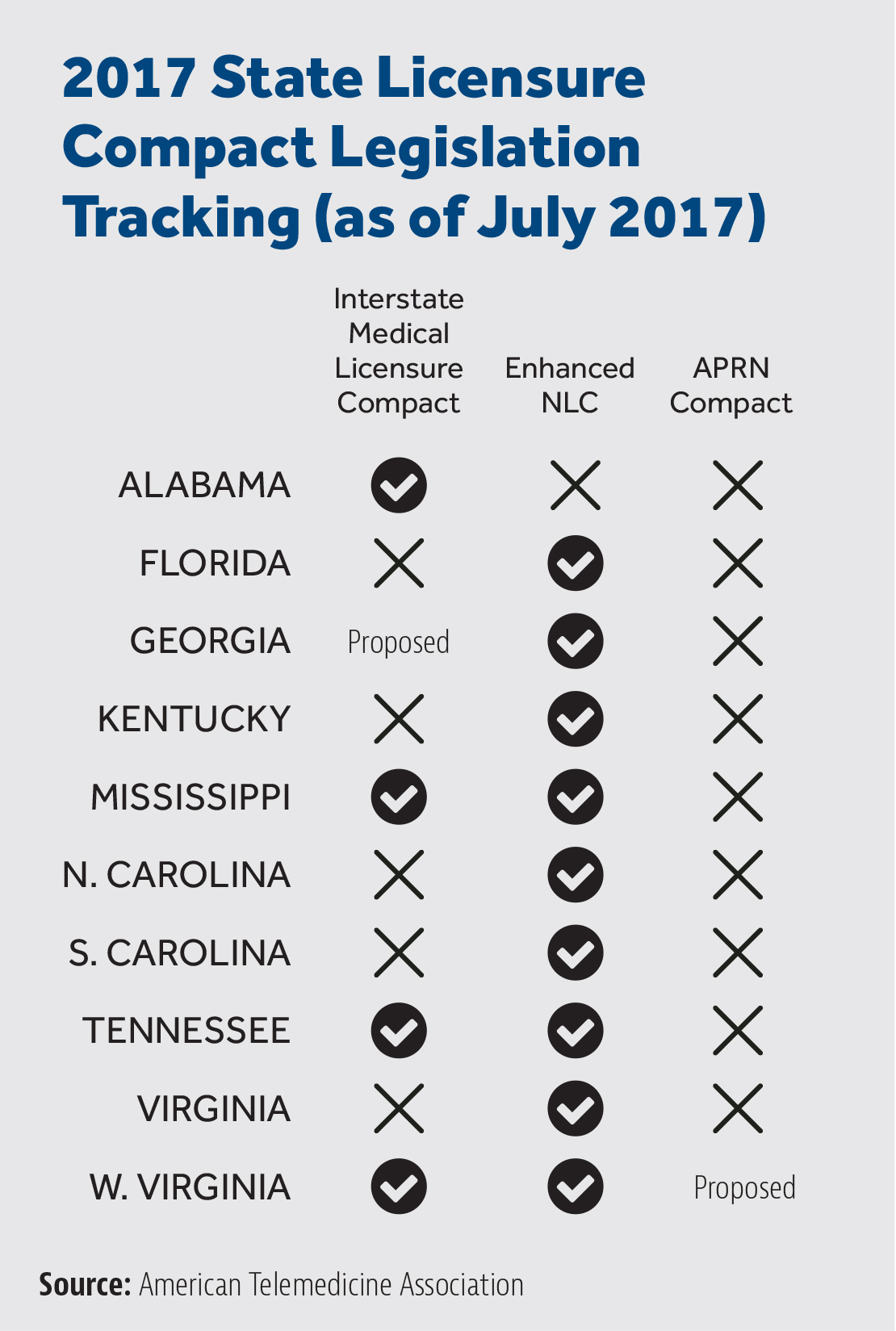

The Board of Nursing is the first regulatory body to promote the expansion of telemedicine across state lines by enacting interstate licensure under the Nursing Licensure Compact (NLC). Since 2000, North Carolina nurses have been given the opportunity to practice in other compact states.90 At the close of the 2017 legislative session, Gov. Roy Cooper signed off on enhanced NLC language that reduces the costs involved for nurses to qualify for a multistate license.91 Rather than paying for separate state licensing fees, nurses need only pay costs for one license that permits them to practice in their home state in addition to 25 other compact states. However, they are still held to other states’ practice guidelines when treating out-of-state patients.92 93

Intrastate Reforms

In 2014, the North Carolina Medical Board revised its position on telemedicine so that physicians could prescribe medications to a patient virtually without being required to conduct an initial in-person exam. It also holds the position that telemedicine is not to be considered its own specialty, but is part of a physician’s standard of care.94

Opportunities and Conclusions

Opportunity #1: Interstate medical licensure compact

Opportunity #1: Interstate medical licensure compact

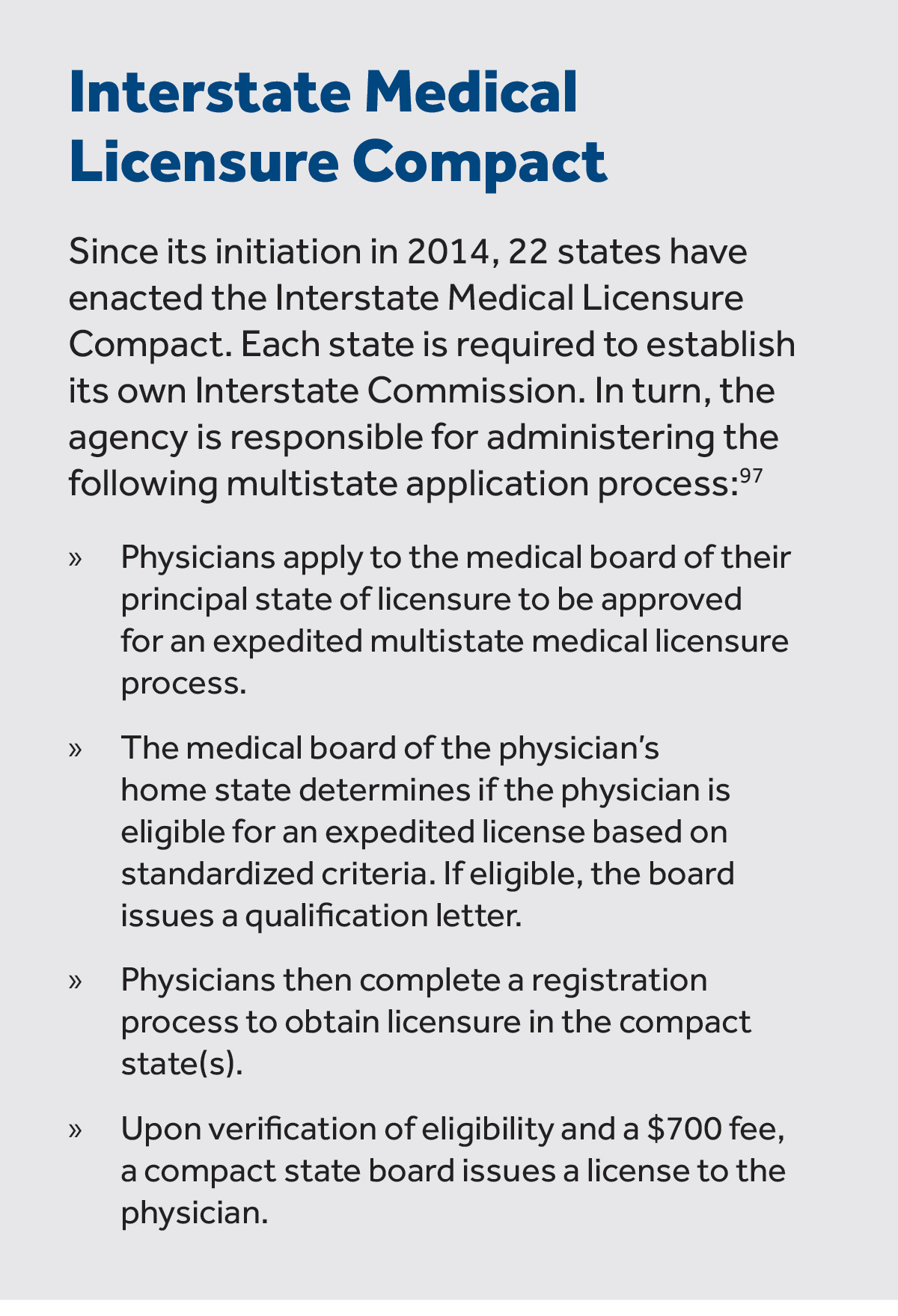

Moving forward, policymakers can also consider legislation for North Carolina to become an affiliate of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).95 96 Sponsored by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), the compact permits physicians to pursue an expedited medical licensure process if they choose to practice medicine – including telemedicine – in other compact states.

The pathway to secure multiple state medical licenses is supposedly more streamlined because information such as criminal background checks or educational credentials does not need to be submitted with each compact state’s medical licensure application. Interested physicians also do not need to wait to receive an expedited license in one compact state before applying to practice medicine in another compact state. They can apply to be licensed in multiple states at one time.98

While the IMLC expedites the medical licensing process, it’s important to mention that physicians are still bound to each compact state’s rules on the practice of medicine and telemedicine. Thus, the compact doesn’t allow for portability. It upholds the standard that physicians can deliver care only to patients who are in states where they are licensed. These restrictions could distance physicians from opting into the compact.

If North Carolina lawmakers do pass model legislation to create an Interstate Commission, it’s paramount that the agency’s appointees make it attractive for physicians to the extent that it can. For example, it would be wise to keep application and renewal fees to a minimum.

Opportunity #2: Remove the need for interstate licensure compacts

Opportunity #2: Remove the need for interstate licensure compacts

To make the telemedicine marketplace more accessible and competitive, a simpler policy solution would be for the state legislature to urge Congress to pass a law stating that the practice of telemedicine be tied to where the provider is located, not to the patient.99 As previously mentioned, physicians can deliver telemedicine only to patients who are physically located in the state where the provider is licensed. If payment is instead tied to the provider’s location, then the provider could deliver care to patients anywhere. Such a policy change would completely obviate the need for the interstate medical licensure compact because physicians would merely have to comply with one home-state medical license.100 Removing cumbersome and expensive licensure barriers would fulfill telemedicine’s mission to democratize access to health care.

In sum, while this report recommends that lawmakers consider legislation that would make North Carolina an affiliate of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact, participation should be considered if Congress fails to pass a law specifying that telemedicine occurs where the provider, not the patient, is located. As mentioned above, this would allow providers to deliver care to patients anywhere, that is, allow health care providers to serve patients across state lines.

Conclusion

Our health care system is a legal and regulatory labyrinth created by Congress and federal bureaucrats that reflects their unwillingness to allow insurers, providers, and consumers to operate freely in the marketplace. Instead, they are subject to regulations so convoluted and voluminous that violating some minute and likely contradictory provision is all but guaranteed.

State lawmakers need not follow suit. States are the last line of defense for sustaining the remnants of a market recklessly imperiled by the federal government and eventually rebuilding a health care system that is responsive to the needs of providers and consumers.

When it comes to a telemedicine parity law, I am proposing a radical course of action for the North Carolina General Assembly – do nothing. Telemedicine will continue to thrive in North Carolina without a parity law.

If given a choice between the free market and adding a law or mandate to the health care system, government should err on the side of the free market.

APPENDIX A: Southeastern State Parity Law Trends

| State | Telemedicine Parity Laws | Political Feasibility | Parity | Telemedicine Modality | Access Limitations | Terms & Conditions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Date of Passage | Amendments | Political Feasibility | Coverage | Specific Coverage Parity language | Payment | Live Video | Store-and-Forward (Asynchronous) | Remote Patient Monitoring | Site | Provider | Geographic Rural/Urban | Y | N |

| Georgia | 2005 | N/A | Y | subject to terms and conditions of insurer | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N (law specifically mentions to mitigate geographic discrimination) | X | ||

| Kentucky | 2000 | N/A | Y | out-of-pocket costs shall not exceed in-person visit consistent with plan design | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y (insurer does not have to reimburse for telemedicine delivered outside state's telehealth network) | Y (insurer does not have to reimburse for telemedicine delivered outside state's telehealth network) | N | X | ||

| Mississippi | 2013 | 2014 (Store-and-forward technologies and remote patient monitoring services added) | unanimous approval | Y | out-of-pocket costs shall not exceed in-person visit consistent with plan design | N | Y | Y | Y (however, payment is conditional to type of patient and RPM equipment. Payment is also capped) | N | N | N | X | |

| Tennessee | 2014 | 2017 (Schools added to list of qualified telemedicine site locations) | near unanimous support | Y | out-of-pocket costs sharing requirements similar to in-person services | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N (2017: parity law amended to prevent geographic discrimination on telemedicine services) | X | |

| Virginia | 2010 | 2015 (amendment to allow prescribing via telemedicine) | near unanimous support | Y | out-of-pocket costs shall not exceed in-person visit consistent with plan design | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | X (however, subect to external review for denied telemedicine claims) | |

Endnotes

- Merritt Hawkins 2014 Survey: Physician Appointment Wait Times and Medicaid and Medicare Acceptance Rates. 2014.

- Thomas Bodenheimer, M.D., and Laurie Bauer, R.N., M.S.P.H. “Rethinking the Primary Care Workforce — An Expanded Role for Nurses.” New England Journal of Medicine. Sept 15, 2016.

- “Closing The Gaps In The Rural Primary Care Workforce.” National Conference of State Legislatures. 2017.

- “Meeting The Primary Care Needs Of Rural America: Examining The Role Of Non-Physician Providers.” National Conference of State Legislatures. 2017.

- “Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs).” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. December 31, 2016.

- Katherine Restrepo, “As Senate GOP Fumbles Health Reform, Telemedicine Delivers Better Access To Health Care.” Forbes. July 27, 2017.

- “History of Telemedicine.” MD Portal. Sept. 23, 2015.

- Marilyn J Field, “Telemedicine: A Guide To Assessing Telecommunications for Health Care.” Institute of Medicine. National Academies Press. 1996.

- Jacqueline Howard, “The doctor will ‘see’ you now: Online vs. in-person vision tests.” CNN. March 15, 2017.

- Katherine Restrepo, “Telemedicine Pairs Well With Direct Primary Care.” Forbes. Sept. 18, 2017

- Sheila Fifer, PhD, Wendy Everett, ScD, Mitchell Adams, Jeff Vincequere, “Critical Care, Critical Choices: The Case for Tele-ICUs in Intensive Care.” The Massachusetts Technology Collaborative and The New England Healthcare Institute. December 2010.

- Kate Blackman et al, “Telehealth Policy Trends and Considerations.” National Conference of State Legislatures. Dec. 2014.

- G Flodgren, A Rachas, AJ Farmer, M Inzitari, S Shepperd, “Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015.

- John C. Fortney et al, “Practice-based versus telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression in rural federally qualified health centers: a pragmatic randomized comparative effectiveness trial.” American Journal of Psychiatry. April 2013.

- Center for Connected Health Policy, “Telehealth Private Payer Laws: Impact and Issues.” Milbank Memorial Fund. August 23, 2017.

- “Telemedicine Mandates and Parity in the Private Market: Summary of State Laws.” America’s Health Insurance Plans. Sept. 30, 2014.

- Telemedicine Regulations in Georgia. Chiron Health. 2017.

- Tennessee House Bill 1895. 2014.

- Center for Connected Health Policy, “Telehealth Private Payer Laws: Impact and Issues.” Milbank Memorial Fund. August 23, 2017.

- “State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies.” Tennessee. Center for Connected Health Policy. April 2017.

- “State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies.” Mississippi. Center for Connected Health Policy. April 2017.

- Matthew Loughran, “Telemedicine Reimbursement Laws Challenge Insurers and Providers Alike.” Bloomberg News. Oct. 17, 2017.

- Kentucky Telehealth Administrative Regulations. Accessed Sept. 10, 2017.

- “State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies.” Georgia. Center for Connected Health Policy. April 2017.

- Nathaniel Lacktman, “Examining Payment Parity in Telehealth Laws.” Health Care Law Today. Aug. 13, 2015.

- “Telehealth Parity Laws. “ Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. Aug. 13, 2015.

- “State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies.” Georgia. Center for Connected Health Policy. April 2017.

- Nathaniel Lacktman, “Examining Payment Parity in Telehealth Laws.” Health Care Law Today. Aug. 13, 2015.

- “Laws and Regulations for Telehealth.” Mississippi Telehealth Association. Accessed Sept 2017.

- Senate Bill 2646. Mississippi Legislature 2014 Regular Session. July 1, 2014.

- Neil Versel, “Mississippi telehealth, remote monitoring pays dividends for diabetics.” Sept. 13, 2016. MedCity News.

- Center for Connected Health Policy, “Telehealth Private Payer Laws: Impact and Issues.” Milbank Memorial Fund. August 23, 2017.

- Kentucky TeleHealth Update provided by the Kentucky Health Information Exchange. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- Kentucky Telehealth and Telemedicine Laws. Kentucky Telehealth Board. May 2017.

- “Telemedicine Mandates and Parity in the Private Market: Summary of State Laws.” Kentucky. America’s Health Insurance Plans. Sept. 30, 2014.

- Telehealth: Helping Hospitals Deliver Cost-Effective Care. American Hospital Association. April 22, 2016.

- Ana B. Ibarra,“Are Virtual Doctor Visits Really Cost-Effective? Not So Much, Study Says.” Kaiser Health News. March 7, 2017.

- Eric Wicklund, “Kaiser CEO: Telehealth Outpaced In-Person Visits Last Year.” mHealth Intelligence. Oct. 11, 2016.

- Katherine Restrepo, “Telemedicine Pairs Well With Direct Primary Care.” Forbes. Sept. 18, 2017.

- Tony Yang, “Telehealth Parity Laws.” Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. August 15, 2016.

- Latoya Thomas and Gary Capistrant, “State Telemedicine Gaps Analysis: Coverage and Reimbursement.” American Telemedicine Association. Feb. 2017.

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, “Telemedicine Study and Recommendations. SL 2017-133, Section 2.” October 1, 2017.

- House Bill 283. North Carolina General Assembly Session 2017.

- Katherine Restrepo, “Want Affordable Health Insurance? Scale Back on Benefit Mandates.” John Locke Foundation. June 14, 2017.

- Darcie Dearth, “The Big Telemedicine Trend: More Coverage, New Innovations In NC.” Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Blog. Aug. 19, 2015.

- Aditi Pai, “UnitedHealthcare Now Covers Doctor On Demand, American Well Video Visits Too.” mobi health news. April 30, 2015.

- John Murawski, “Durham startup TouchCare’s telemedicine service gains key backer.” News & Observer. Dec. 20, 2014.

- Jennifer Henderson, “Durham telemed startup has new mental health partnership.” Triangle Business Journal. Dec. 7, 2016.

- “State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies.” North Carolina. Center for Connected Health Policy. April 2017.

- “Realizing the Promise of Telehealth: Understanding the Legal and Regulatory Challenges.” American Hospital Association. May 2015.

- RelyMD.

- Amy Huffman, “Can ER Doctors’ Startup Make Telehealth Ubiquitous in North Carolina and Beyond?” ExitEvent. April 27, 2016.

- “Average wait time to schedule physician appointment longest in Boston.” Healio. Jan 29, 2014.

- Steve Huffman, “RelyMD partners with Piedmont Health for after-hours coverage.” Triad Business Journal. Dec. 2, 2016.

- Katherine Restrepo, “Direct Primary Care: A Simple Health Care Model Designed To Help Patients With Chronic Disease and Disabilities.” John Locke Foundation. March 22, 2017.

- David Craig, “Spruce Visits: Improve Your Practice with Efficient Telemedicine.” Spruce Blog. July 20, 2016.

- David Craig, “Spruce Visits: Improve Your Practice with Efficient Telemedicine.” Spruce Blog. July 20, 2016.

- Roy PC Kessels, PhD, “Patients’ Memory For Medical Information.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2003.

- Frank Irving, “E-consults Hold Promise For Efficient PCP And Specialist Interaction.” Healthcare IT News. Nov. 29, 2011.

- RubiconMD.

- “Evolution of Consumer Driven Health Plans Blog Series: Part 2.” Paladina Health. January 20, 2016.

- Sheila Fifer, PhD, Wendy Everett, ScD, Mitchell Adams, Jeff Vincequere, “Critical Care, Critical Choices: The Case for Tele-ICUs in Intensive Care.” The Massachusetts Technology Collaborative and The New England Healthcare Institute. December 2010.

- “Virtual ICUGoes Live at Blue Ridge HealthCare.” Dec 4, 2013. YouTube.

- Jennifer Thomas, “Carolinas HealthCare adds virtual component to intensive care.” Charlotte Business Journal. May 2, 2013.

- Sheila Fifer, PhD, Wendy Everett, ScD, Mitchell Adams, Jeff Vincequere, “Critical Care, Critical Choices: The Case for Tele-ICUs in Intensive Care.” The Massachusetts Technology Collaborative and The New England Healthcare Institute. December 2010.

- Michael Tomsic, “Staffing An Intensive Care Unit From Miles Away Has Advantages.” National Public Radio. May 6, 2015.

- “Virtual Critical Care.” Jan 12, 2017. YouTube.

- Eric Wicklund, “Mercy Virtual Aims for a National Telemedicine Network.” mHealth Intelligence. Feb. 12, 2016.

- Julianne Pepitone, “The $54 Million Hospital Without Any Beds.” CNN Money. Sept. 13, 2016.

- Eric Wicklund, “Mercy’s Telemedicine Network Is Growing.” mHealth Intelligence. May 23, 2016.

- The Philanthropic Women’s Society: Southeast Alabama Medical Center Foundation

- Southeast Alabama Medical Center Foundation. Itemized List of Donations, inclusive of stroke initiative telemedicine units.

- Southeast Alabama Medical Center Stroke Care Network Powerpoint Presentation. Alabama Rural Health and TeleHealth Summit. Oct. 17, 2013.

- Amy Yurkanin, “Dialing up the doctor: Telemedicine gets a vital boost in Alabama.” AL.com. March 14, 2016.

- Eric Wicklund, “It All Adds Up: Telestroke Services Save Lives.” mobi health news. July 1, 2013.

- Katherine Davis, “Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama will pay for telemedicine services.” Modern Healthcare. December 1, 2015.

- Erica Garvin, “Teladoc’s CEO Talks What Telehealth Means for the Future of Healthcare.” HIT Consultant. December 9, 2015.

- Amedeo d’Amore, “11 top telemedicine businesses that can help save healthcare.” Hottopics.HT. Accessed Sept. 18, 2017.

- Brian Bandell, “MDLIVE to hire dozens in Sunrise after partnership with Cigna.” South Florida Business Journal. April 23, 2013.

- Eric Wicklund, “Cigna announces telehealth partnership with MDLive.” mobihealth news. April 23, 2013.

- Jessica Harper, “Pros and Cons of Telemedicine for Today’s Workers.” U.S. News & World Report. July 24, 2012.

- MDPlus.

- Dawn Brazell, “MUSC receives $12.4 million for telemedicine program.” Medical University of South Carolina Public Affairs and Media Relations. Aug. 2, 2013.

- “Telemedicine Improves Access to Care in SC.” South Carolina Hospital Association.

- Marina Ziehe and Tabitha Safdi, “Technology Extends Health Care to S.C. Schools.” South Carolina Public Radio. April 3, 2017.

- Reed Abelson, “American Well Will Allow Telemedicine Patients to Pick Their Doctor.” The New York Times. My 16, 2016.

- Brittany Murray, “iSelectMD, PEIA partnership to provide telemedicine services for over 180,000 members.” The Exponent Telegram. Feb. 12, 2017.

- “Charleston Area Medical Center Reduced Congestive Heart Failure Readmissions with Patient Engagement Technology.” Telehealth Services Press Release. Feb. 9, 2017.

- Taylor Mallory Holland, “How Patient Entertainment Systems Boost Satisfaction and Health Outcomes.” Insights. April 29, 2016.

- Nurse Licensure Compact. North Carolina Board of Nursing. Accessed October 17, 2017.

- “Governor Cooper Signs HB 550 – Enhanced Nurse Licensure Compact.” North Carolina Board of Nursing Press Release. July 21, 2017.

- Nurse Licensure Compact: Fact Sheet for Faculty and Students. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- Pulse Clinical Alliance, “Decompressing The Enhanced Nurse Licensure Compact Changes.” Pulse Clinical Alliance. July 17, 2017.

- Michael H Cohen, “Telemedicine prescribing position softened by North Carolina Medical Board to allow virtual examination and evaluation.” Michael H Cohen Healthcare & FDA Lawyers. Dec 1, 2014.

- Interstate Medical Licensure Compact Model Legislation. Accessed Sept. 10, 2017.

- Interstate Medical Licensure Compact:

- Interstate Medical Licensure Compact:

- Katie Dvorak, “Interstate medical licensure compact will save physicians time, effort.” Fierce Healthcare. April 24, 2015.

- Shirley V. Svorny, “Liberating Telemedicine: Options to Eliminate the State-Licensing Roadblock.” Cato Institute. Nov. 15, 2017.

- Shirley V. Svorny, “Liberating Telemedicine: Options to Eliminate the State-Licensing Roadblock.” Cato Institute. Nov. 15, 2017.